|

The ‘Castellu di la Chitati’ |

|||||||||||

| by Stephen C Spiteri | |||||||||||

|

One of the least understood of all the works of fortification to have stood watch over the Maltese islands in antiquity is the castellu di la chitati (1) - the medieval castle of the old town of Mdina. The arcanum that surrounds this ancient stronghold stems primarily from the fact that it was dismantled way back in the 15th century and what little had remained of the building thereafter, eventually disappeared altogether in the metamorphosis that accompanied the Hospitaller re-fortification of the medieval town into a gunpowder fortress throughout the course of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries. This, coupled with the limited nature of contemporary documentary information, has ensured that the true form and features of the medieval stronghold have been lost to the point that now only archaeology can hope to really figure out.

It is has long been recognized that the medieval fortifications of Mdina consisted of two main defensive elements - a fortified town and a castle. Gio. Francesco Abela pointed this out in his Della Descrittione di Malta as far back in 1647. (3) Contemporary medieval archival documentation has been shown to differentiate between the two entities, referring to the town as the castrum civitatis malte and the castle as the castellu di la chitati (4) (nonetheless the distinction between the two is sometimes dropped). The word castrum was originally applied to large fortified Roman military camps but came to be used to describe most walled towns or other fortified settlements of a non-purely military nature throughout the middle ages. The castellu, or castellum, on the other hand represents the low Latin diminutive of castrum and refers to a type of fort, although it also came to be applied to a specialized fortified structure that appeared with the formation of a new social organization in the middle ages. (5) At Mdina, these two fortified entities seem to have been closely interwoven, such that the walls of one were coterminous with those of the other. (6) Together they occupied a relatively small area at the tip of a strategically sited plateau - part of the site which once served to accommodate a much larger Roman, and earlier Punic, fortified town. (7) This site, standing as it is at the very heart of the island, was a natural focal point of refuge commanding clear views of the greater part of the island's coastline. Inhabited since prehistoric times, it appears to have originated as one of the island's fluchtorte (8) established during the insecure Bronze Age period until it eventually rose in importance as a settlement to become the dominating administrative and political centre in Punic and Roman times. Given this continual process of occupation and settlement, the first difficulty besetting the study of the medieval defences of Mdina is precisely that of establishing some kind of date for the transformation of the Roman city into the medieval fortress. As yet, this is still very much an obscure process. The abandonment of the greater part of the larger Roman enceinte for a smaller and more easily defensible perimeter was a common enough phenomenon throughout the Mediterranean in the troubled and insecure times that followed the collapse of the Roman empire, characterized by a significant shrinkage in urban populations. Inevitably, the ancient city itself came to be responsible for much of the character of the subsequent fortress for it provided the site, possibly a large part of the lateral walls and most of the building materials for the construction of the medieval ramparts. The lack of any precise knowledge of this process of transformation, however, has seen most historians take refuge behind the popular notions that accredit the establishment of Mdina's medieval enclosure to either the Arabs or the Byzantines, or both. Determining this particular point, however, is of fundamental importance to the study of the medieval fortifications of Mdina, and is particularly crucial to understand the nature and development of the castellum. Archaeological evidence tends to suggest that the medieval front was definitely in existence by the late Arab period. The presence of a late Muslim cemetery extra muros not far from Greek's Gate (near the Roman town-house), together with the toponymy of Mdina itself, (derived from 'Medina', Arabic for fortified city) has always been taken as proof that it was the Arabs who had redefined the city's layout, establishing its present form.(9) However, this need not necessarily be the case for the Arab occupation of Malta seems to have been accomplished over a period of time following a succession of brazen raids from nearby Sicily. Archaeological remains at Tas-Silg, for example, have shown the presence of various destruction layers and hastily built defensive walls around the Byzantine structures dating to around the 8th century. (10) The same process of retrenchment may have occurred at the town of Melita, where the Byzantine garrison, under increasing Arab pressure could have been compelled to rationalize the defence of the large town reducing it to more defensible proportions over a period of a few decades by pulling back the front to a narrower part of plateau, exploiting any defensive topographical features to such effect and reinforcing it with a fort. A Byzantine origin, then, could imply that the latter medieval castle, rather than having been built de novo in Swabian times, as has been suggested, (11) may have probably emerged from the foundations of a Byzantine fort.

As a matter of fact, the qualities of the site are much in keeping with the nature of a Byzantine military fort of the pyrgokastellon (purgokastellon) type. This, although housing the governor and his garrison, would not have been a castle in the true later sense of the word but a predominantly military establishment concerned primarily with defence rather than political control. The word is coined from pyrgos, Greek for tower, and castellum, Latin for fort and typifies a nodal strongpoint, similar to the Frankish keep but designed to reinforce the weakest part of the enceinte as prescribed by Procopius. (13) In the words of T. E. Lawrence, the Greeks put their keeps and castles 'where they were wanted, the Franks where they would be impregnable.' (14) And truly, the southeast corner marked the most sensitive part of Mdina's enceinte, overlooking the ascending approaches from the surrounding plains up the Saqqajja. One can find an excellent parallel in the Castello Gioia del Colle in Puglia, founded by Richard Seneschal, brother of Robert Guiscard on a pre-existing Byzantine fort which was later enlarged by Roger II and rebuilt by Frederick II around 1230. The Arabs on their part are traditionally ascribed with having begun the excavation of the main fosse that isolated the castrum from the rest of the mainland. Significant efforts to establish the ditch as an effective defensive feature, however, were still underway during the mid 15th century so the Arab intervention could not have involved much more than the exploitation of an existing natural depression.(15) – as a matter of a study of the bed-rock beneath the bastion walls does reveal a drop between the two extremities of the front in the direction of Greek's Gate. But apart from the presence of a few rounded walls towers, as depicted in early 16th century plans, there is very little else that can possibly point to their handiwork in the formation of the castellu. Arab preference was for citadels rather than castles - large fortified and turreted enclosures. Still, any available Byzantine kastron would have been readily utilised - witness the citadel of the fortress of Tripoli captured by the Spaniards in 1510. (16)

The fasil, therefore, was equivalent to the intervallum, the fighting space between two walls - the currituri quoted by Fiorini/Buhagiar. (19) This definition holds important implications, for it immediately hints that Mdina, or at the least a considerable part of the town, was enclosed within a set of two walls - a common enough feature in the fortified towns of the period. In other words, the Mdina ramparts consisted of a main wall, a teichos (teicos), and a lower outer wall - the proteichisma (proteicisma) or antemurale - much better understood today as the falsabraga or faussebraye. (20) The definition of fasil as a 'fortified wall capped by a parapet' is, in my opinion not exact, and any reference to a low parapet (parapetto basso) as given in Amari's translation of at-Tijani, (21) should be read as the low outer wall or antemurale, for a fortress dependent solely on a low parapet for its defence would have had very little chance of survival. The need for an antemural was necessary to protect the base of the main wall itself, both as an added safeguard against mining and direct assault, and as a buffer against siege towers. Again, it finds its inspiration in Byzantine military architecture, particularly in the Theodosian walls of Constantinople. Actually, one of the best surviving examples of the system of double walls built during the 14th and early 15th centuries is to be found along the southern part of the enceinte of the Hospitaller fortress of Rhodes. (22) Fiorini/Buhagiar place the fasil, on the basis of their reading of the medieval documents, on the northern part of the enceinte in the Salvatur area, identifying the present raised chemin-de-ronde and embrasured parapet with the fasil. (23) There is no doubt that there was a fasil along this part of the enceinte but it is more likely, however, that this feature was enclosed by the present outer vertical wall and an inner secondary wall, as hinted by the massive block of solid masonry surviving inside the nearby Beaulieu House. It is also possible, on the other hand, that the fasil could have been outside the present vertical rampart for the French military engineer Charles Francois de Mondion, involved in the reconstruction of Mdina's fortification in the early 18th century, records the presence of the remains of ancient outer walls at the foot of the northern ramparts, '... quali vestigi non solamente si vedono nel detto fondo ma anche si distendono fin quasi il posto baccar dove s'attacano con il roccame che resta scoperto sotto le mura di essa Città.' (24)

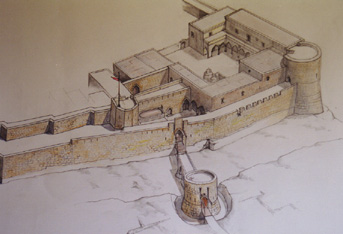

The D'Aleccio and Serbelloni plans, actually provide the only convincing graphic clue to the planimetric layout of Mdina's medieval fortifications. These show the location of the town's four towers and double set of walls, the two gates and the remains of the castle itself . By the mid-16th century, however, the brunt of the town's defences had then come to rest on two new corner bastions begun during the reign of Grand Master D'Homedes even though much of the intervening medieval defensive elements were still intact. It was only the castle that was missing from the equation, its place taken over by the new magistral palace. The disappearance of the medieval stronghold entails no enigma. It was pulled down by royal licence in response to local demand some time after 1453. (27) The excuse was not some Lacedemonian policy of not fortifying the place but that its old ruinous walls had become a public danger and, apparently, its upkeep a significant drain on the town's purse; possibly it had come to be a despised tool of tyrannical oppression, especially under the Chiaramonti. Evidently, as a work of fortification, it must have offered very little command and defensive advantage for the town elders to request its dismantling at a time when the Island had begun to attract the increasingly hostile attention of Barbary corsairs. Only some twenty years earlier, in 1429, a force of 18,000 men under Qâ'id Ridwân had invaded the island and all but captured the city after subjecting it to a siege.(28) Actually, the Castellu dili Tyranni (29) was only partially demolished since it was just the internal walls separating it from the town that were pulled down and the masonry used to repair the town ramparts and gate. The castle's outer ramparts and towers, which formed an integral part of the main enceinte, were obviously retained. In fact, that part of the castle which was embodied into the land front contained at least two towers and a gateway. Both are clearly indicated in 16th century plans. The tower to the left of the main gate (when seen from outside), was known as the Turri Mastra (30) and controlled the entrance and exit into the fortress - this structure was eventually replaced in the early 18th century by the Torre dello Standardo though the this retained the original role as a watch-out/ signalling post. The Turri Mastra, or Turri dila bandiera, seems to have been rectangular in plan with a polygonal or semicircular front. Only in one late 17th century plan, very roughly executed, is it shown as having had a circular form. (31) The tower to the right of the main gate occupied the south east extremity of the land front - the most sensitive part overlooking the approaches from Saqqajja. It is no coincidence, therefore, that the plans show it to have been the most solidly built of all the town's turri, having markedly thicker walls. In all likelihood this was the Mastio, the strong tower or keep of the castellu (see illustration A). In the documents it is referred to as the Turri di la Camera (32) - a faithful description when one sees how it was integrated with the adjoining palatial halls. By the 16th century this massive tower was linked to the magistral palace in a manner that still recalled a corner tower attached to a rectangular ward - the whole layout reminiscent of many rectangular Swabian castra erected by Frederick II in Apulia such as those of Bari, Gioa del Colle, Trani, Barletta and Monte Sant Angelo. (33) The palazzo built by L'Isle Adam after 1530, with its arched porch, seems to have occupied the undemolished east wing of the castle's ward, that part of the stronghold which must have served as the residential quarters of the capitaneus civitatis. This was probably achieved much in the same way that the Grand Master's other palace at the Castrum Maris replaced the former castellan's house there. Indeed, it appears that even as early as 1413, the Mdina stronghold was already serving more as a captain's residence rather than for defensive purposes. (34) Vestiges of the facade of L'Isle Adams new pallaso, seem to have actually survived within part of the courtyard rebuilt by the French Engineer Mondion in the 1720's as part of the remodelling of the Magistral Palace complex. The presence of a very thick wall, with blocked-up apertures and truncated windows having delicately moulded surrounds (see photographs) hint at the remains of a 16th century building. Indeed, the inner courtyard itself, remodelled by Mondion, seems to have respected the footprint of the old castral ward. It is not yet clear, however, if the vaulted rooms at ground level (the hospital kitchen) enveloping the courtyard, particularly those to the east and south - one of which is threatening to collapse - actually date back to 15th century or much later. What is clear from the contemporary plans is that L'Isle Adam's palace overlooked the courtyard, was fronted by an arcaded portico and was approached via the narrow street leading to the present day Xaghra Palace. The rounded tower itself continued to feature in the plans of Mdina well into the early 1700s until the magistral palace was finally rebuilt by Mondion. Judging by the D'Aleccio /Serbelloni plans, the left flank of the D'Homedes bastion was actually grafted onto this tower. It remained visible until it was buried beneath a heavy buttress laid onto the outer wall at the foot of the magistral palace - an intervention which actually blocked-up one of the two embrasures in the same flank of the adjoining bastion itself.

the bastion was erected. Fitted with vertical and horizontal flues, the gallery was designed to dissipate the blast of an explosive mine fired beneath it walls. This feature is missing in the belguardo dila Porta dili Grechi on the opposite end of the land front, a bastion which was built many years later. One other reason that was cited in favour of the demolition of the castle's inner walls in 1453, was the need to open up new public space for settlement by people from the surrounding countryside. However, if the castellated enclosure was merely restricted to the area of the present magistral palace, than this could not have possibly attracted many new residents. Ergo, the castle's inner walls may have extended further northwards towards the Cathedral, possibly in the form of a lesser ward. Initially, these may have even linked up with the Rocca recorded to have existed on the northern part of the town. (37) Still, the Rocca, evidence of which appears to have survived in a massive wall inside Beaulieu House, may more likely than not have been a detached strong-point in its own right, as the definition of the word surely implies. In that case, however, it is difficult to explain the presence of a secondary stronghold within the perimeter of such a small fortified town as Mdina unless, of course, this was merely the vestige of some former, probably pre-medieval, fortified structure. Recent excavations undertaken at Xaghra Palace, just outside the Magistral Palace to the north, have revealed the presence of solidly built perimeter walls, composed of large blocks of masonry, all dating to Roman or Punic times, but evidently re-laid in medieval times. Actually, nothing of the medieval ramparts along the east flank of Mdina seems to have survived above ground level for the old town walls were rebuilt en cremaillere by the Knights. The Order's resident military engineer, Blondel, writing in 1693, tells us that all that part of the town's perimeter 'volta a gregale e levante sino al Palazzo suo magistrale … fu rinovata tutta quella cortina dal Gran Maestro Omedes'. (38) By the late 17th century, however, many town houses had also encroached onto these walls such that direct access to the ramparts was not possibile '...se non per di dentro alle case de particolari, non solo appoggiate ma attaccate, et alle quali serve elle di muro esterno' - the house of the Muscat family, for example, even had latrines, 'gabinetti su l'orlo del bastione'.(39) All this was done to the detriment of the town's defences and in 1717 it was felt necessary to impose upon the Cannons of the Cathedral Chapter the condition that any new windows cut into the ramparts in the course of the rebuilding of the Archbishop's palace had to be made '...in forma di cannoniere capaci di ricevere canone secondo il bisogno'. (40) That part of the outer wall adjoining the magistral complex seems to have began to suffer from serious subsidence of the ground soon after the Vilhena's palace was rebuilt in the early decades of the 18th century. As a result, it was found necessary to reinforce the wall with a large masonry buttress, massiccia d' appoggio.- now itself peeling off.

The gates themselves would have been of the type still to be seen at Greeks Gate, on the other end of the Mdina front - with a vaulted pointed arch of horseshoe profile. The present walled-up gate to the right of the main baroque entrance marks the exact site of the original medieval entrance but its boxed rectangular mouldings and rusticated pilasters indicate an early 17th century reconstruction. In 1527, the main gate was decorated with the coat-of-arms of Sua Cesarea MaJestati, carved in stone by Maestro Jayme Balistre[ra] (44). Both the main entrance and Greeks Gate were served by wooden drawbridges approached over stone ponti. It is not possible to say what type of lifting mechanism was employed - Greek's Gate itself gives no such clue. The bascule type of drawbridge with wooden arms, however, was the most common type employed throughout the middle ages for its simple counterweight mechanism. The bascule was also much favoured throughout the 17th century and can still be seen at St. Thomas Tower in Marsascala. The lifting mechanism at Mdina definitely comprised the use of wooden beams, 'bastaso che levao lu ponti' (45) and metal chains, for in 1527 a cantaro di ferro was purchased to produce the 'catinj dilo ponti'. The drawbridges themselves were made from planks of oak (46) at one time brought purposely from Messina and judging by the entries in the records were continually in need of repair, particularly that at Greeks Gate. There also seem to have been posterns and sally ports for sorties and furtive getaways, but no vestiges have survived, as has remained, for example, on the medieval ramparts of the Cittadella in Gozo. Contrary to what has been stated, however, the written records do in fact allude to their existence. The mandati documents of 1527, for example, refer to the 'porta falsa Jpsius civitatis' - porta falsa (or falsa porta) is a term used frequently to refer to sally-ports or posterns and is encountered even on 18th century plans of the Order's fortifications. (47) Another entry in the mandati is even more specific, mentioning the need to wall up an exit into the ditch, 'murari la porta dila putighia (magazine) che apri alo fossato'. (48) A most interesting feature of the Mdina fortifications, mentioned by Gian Frangisc Abela in 1647 was the presence of a barbican, a 'Torrione forte di forma circolare con fosso e cistrena' that protected the far side of the bridge leading to the main gate. (49) Surprisingly, the medieval documents make no specific reference to this structure. Dr. Albert Ganado, however, citing the history of the Inguanez family revealed that this was built by Antonio Desguanecks sometime after 1448. (50) Giacomo Castaldi's map of Malta (1551), too, shows Mdina with a turreted barbican although the actual details must not be taken too seriously especially when other obvious landmarks are shown so confusingly in the same map. By the 15th century, barbicans were a standard component of most European castles - even the Gozo Castrum had one and this is illustrated in D'Aleccio's plan. It was also the convention to depict castral entities with such features. In any case we known that Mdina's barbican was actually dismantled in 1551 because it was then considered more of a liability than an asset to the city's defence (51); presumably it was too small to serve as a mezzaluna in the age of gunpowder defences and must have obstructed the field of fire from the adjoining ramparts and the newly built D'Homedes bastion. An inventory of Mdina's artillery compiled by Mastro Giullelmo (52) in May 1560 does, however, mentions the need to place cannon a basso al fianco di Barbacana. In this case however, the word 'barbacana' is refering to the bent entrance approach at the foot of the Torri dila Bandera rather than to the tête de ponte built in the mid-15th century since we known that the latter had already been demolished. For although etymologically deriving from the Arabic bab khank meaning gatehouse or gate-tower, the word is also frequently used to describe an antemural. Nonetheless, some sort of minor outerwork seems to have survived in the area, for in 1716 we read of the 'muro che cinge il corpo di guardia avanti la porta'.(53) Little has survived to date of the original fabric of the medieval fortress of Mdina. The only indication of the true nature and texture of the castle's ramparts comes from the sole surviving section of medieval wall still to be seen at Greek's Gate. Apart from the vestiges of the gate itself with its pointed arch there is the adjoining stretch of vertical curtain wall some 3 metres thick and 10 metres in height. This wall is built mainly of coursed rubble-work with increasingly larger stone boulders in the lower courses, many of which appear to have been re-utilised from some earlier Roman, possibly Punic buildings, or ramparts. The practice of cannibalising ancient structures for their building materials is encountered throughout the Mediterrranean during the Middle Ages. To mention one example, the fortress of Bodrum was built with material quarried from the site of the famous Maussoleon at Harlicarnassus. More evidence for the reuse of classical masonry in the medieval ramparts of Mdina has also come up during archaeological excavations in Inguanez Street and Xaghra Palace. The site at Inguanez Street revealed that the old medieval town walls along the land front were constructed with much use of ancient masonry blocks. The walls of the ancient city, particularly in the Rabat area would have provided a good source of building material. In 1724, officials of the Università of Notabile could still write of the presence of a 'pedamento di muro di pietra rustica in the vicinity of Greek's Gate claiming that this wall was quell'istesso che faceva circuito alla città che era grande fin il fosso di S. Paolo extra muros: il gia detto muro continuva per sopra Ghariexem e passa da diversi luochi'. (54) It is difficult to reconcile the texture of the surviving remains with the many references to the repeated use of cantuni and balati employed in the repair and maintenance of the ramparts throughout the 15th and early 16th centuries, since the latter imply walls of more regular ashlar construction such as can be still seen on the projecting rounded wall-tower on Mdina's north wall. Even then, the outer masonry shell of this remnant of a medieval wall tower could actually date to much later Hospitaller times when most of the old walls had to be rebuilt. In 1693, for example, Blondel was still effecting repairs to 'l'anticaglie spolpate e dal tempo smosse, e consumate all'esterno'.(55) Of crenellations, drop boxes, machicolations, arrow-slits, loopholes and gun loops there is no specific hint, neither in the documents nor in the surviving physical remains. However, as a veritable fortress, the ramparts of Mdina would surely have been fitted with many such features. But these, having crowned the crest of the ramparts would have been the first to disappear. If the generous use of well-built galleriji tal-mishun on the Gauci tower erected in the first half of the 1500s by the Captain of the Naxxar militia is anything to go by, then piombatoi seem to have been a regular adjunct of local defences and must have punctuated the ramparts of the island's main fortress with similar ease, particularly in the vicinity of gateways. The presence of similar box-machicoulis on other towers around the island, particularly at Birchircara and Qrendi (Torri Cavalieri), built well into the 16th century, also reflects an insular tendency towards technological drag despite the introduction and widespread use of firearms. The Gozo Citadel too retained various elements that hint likewise although we know that the cause in this case was the Order's reluctance to invest in its re-fortification. The Gauci tower also provides unique examples of cruciform slits cut in the faces of the machicolation for use with crossbows. By the early 16th century, Mdina's garrison contained both balistrieri and scopetieri and its parapets would have been required to provide the necessary facilities for its defenders. Cannon too became an important element in its defence. The documents reveal the presence of many bombardi by the late 15th century. Around that time, these guns would still have been mounted on low static cippi and cavalcature which required apertures, or gun loops, cut low in the parapets in order for the guns to be fired. By 1522, however, the parapets of the fortress may even have begun to be fitted with embrasures to take more modern cannon such as the columbina (culverin) mentioned in the mandati and others types mounted on carriages with loru roti. (56) Despite the increasing reliance on gunpowder artillery for its defence, the fortress of Mdina was still predominantly a medieval stronghold geared towards a medieval form of warfare at the time of the coming of the Knights to Malta in 1530. It remained so, well into the 16th century and only really shed its medieval skin in the early decades of the 18th century when its ramparts, and a large part of its public and private buildings were practically rebuilt anew during the reign of Grand Master Manoel de Vilhena. The extensive nature of that rebuilding programme has meant that very little of the old fortress has survived above ground. The graphic reconstruction of the of Mdina's medieval ramparts presented here is based on the elements discussed above and shows the fortifications as these may have stood in the late 15th and early 1500s prior to the arrival of the Order in Malta.

Author’s NoteI would like to thank Mr. Nathaniel Cutajar BA (Hons) Archaeology MA for his help, guidance, and encouragement in the preparation of this paper, and with whom I also had many opportunities to discuss this subject at length. Some of the ideas presented here actually owe their origin to Mr. Cutajar himself and I hope that he will be developing these further through the course of his own specialized studies in the medieval archaeology of Mdina. I am also grateful to Mr. Paul Saliba BA (Hons) Archaeology, for drawing my attention to certain archaeological and historical facts, the existence of various old texts and other relevant information. References

1.

Archivo di Stato di Palermo

RC 49, f. 51 as quoted in Fiorini & Buhagiar, The defence and Fortifications of Mdina in Mdina the Cathedral City,

vol. II, p. 443 (Malta -

1996). 2.

Fiorini & Buhagiar, op.cit. 2 Vols. 3.

Gio. Francesco Abela, Della

Descrittione di Malta, p. 31 (Malta - 1647).

4.

Giliberto Abbate's report of c.1241,

quoted in Luttrell A., 1992 and note 1

supra.

5.

Monreal Y

Tejada, L., Medieval Castles of Spain,

p.16 (Madrid - 1999).

6.

Acta

Juratorum, doc. 10 (1540) as quoted in Fiorini & Buhagiar, op.cit., p.

443. 7.

Bonanno A., Roman Malta, pp.19-21 (Formia

- 1992). 8. A

naturally defensive site used as a refuge place in times of danger, see

Winter, F.E.,

Greek Fortifications,

p. 16 & footnote

65 pp. 31-32 (Canada - 1971). 9. Azzopardi,

G.,

Papers in Maltese Linguistics, p.216 (Malta –1970): 'Arabic

‘almadina’ is the principal city, the city held in highest regard.'

Other cities bearing the same name are MEDINA (Caccaino & Castronuovo,

Palermo, and Badajoz, Cadiz & Valladoid in Spain), ALMEDINA (Cuidad

Real), ALMEDINILLA (Cordoba), ALMUDINA (Alicante), MADINA (Guipuzcoa);

Cagiono de Azevedo, The

1970 Campaign in Missione

Archaeologica a Malta, Campagna di Scavi 1970,

p.103 (Rome –

1973); ‘… and manifestations even in the late Roman and Byzantine ages, not

only in connection with the church … but also with fortifications and

defensive works, particularly M21, M26, M27,M34 which take us back to the

age of the Arab conquest and testify that it did not happen in one moment,

but rather that it concluded a long series of decades of war’. 10. Al-Himyarî first referred to Mdina as an ancient city inhabited by the Byzantines. In the year 225 (870 AD) the Arabs under Sawada Ibn Muhammad captured the fortress of Malta and demolished it, dismantling many buildings and carrying away the stones to build a castle in Susa. Thereafter the island remained practically uninhabited for some 180 years and was only re-peopled by the Arabs in the year 440 (1048-49 AD) who rebuilt its city to make it ‘ a finer place than it was before’, Brincat, J.M , Malta, 870-1054: Al-Himyarî’s Account, p.11 (Malta – 1991). The Muslim cemetery within the Roman town-house is post 1090 AD, i.e. it dates to after the plunder of the Maltese islands by Count Roger, Trump, D., Malta, An Archaeological Guide, p.23 (London – 1972). 11.

Fiorini & Buhagiar, op.cit.,

p. 444. 12.

ibid.

13.

Procopius of Caesarea, Buildings, ii. 5,8-9, ed.

J. Haury p. 38 (Leipzig -

1913), translated by H.B.

Dewing; London 1940, cited in T.E. Lawrence,

Crusader

Castles p. 27 (Oxford - 1990 edit) edited by Denys Pringle. 14.

Lawrence, op.cit., pp.26-27. 15.

Archives of the Cathedral Museum, Mdina , Misc. 437 cited in

Fiorini & Buhagiar p.458. 16.

Messana G., La Medina di Tripoli in

Quaderni Dell'Istituto

Italiano di Cultura di Tripoli, p. 16 (Roma - 1979); Rossi, E., Storia di Tripoli e Della

Tripolitania Dalla Conquista Araba al 1911, p. 26

(Roma - 1968) 17.

Wettinger, G., The Jews in Malta in the Late Middle Ages, p. 16 (Malta - 1985). 18.

Creswell, K.A.C., A Short Account of Early Muslim

Architecture, p.231, (Scolar Press - 1989 ed. revised and

supplemented by James W. Allen).

Fiorini

& Buhagiar, op.cit., p.450. 19.

Lawrence, T.E., op.cit., pp.27-29

: (Oxford - 1990 edit) edited

by Denys Pringle; Gabriel, A., La

Cité de Rhodes, p. 133 (Paris

- 1921). 21.

Fiorini & Buhagiar, op.cit., foot note 30. 22.

Gabriel, op.cit, pp. 122-133; Spiteri, S.C,.

Fortresses of the Cross - Hospitaller Military Architecture, pp.

77-81 (Malta - 1994). 23.

Fiorini & Buhagiar, op.cit.,

p.452. 24.

National Library of Malta, University of Notabile, Ms.

187 (?) f.76 (1724). 25.

ibid. 26.

National Library Of Malta, University of Notabile, Ms. 12, f.48

(4.xi.1513) mentioned in Fiorini & Buhagiar, op.cit., p.446: For the

Serbelloni plan see Ganado, A., Sixteenth

Century Manuscript Plan of Mdina by Gabrio Servelloni in Mdina

and the Earthquake of 1693 ed. by J. Azzopardi, pp.77-83

(Malta - 1993). 27.

Abela, op.cit., p.31; for a more detailed evaluation of this aspect

see Fiorini & Buhagiar pp.443-445. 28.

Mifsud 1918-19. 29.

Archives of the Cathedral Museum, Mdina,

Misc. 27 as cited in Fiorini & Buhagiar, op.cit., p.445. 30.

Mifsud, A., La Milizia e Le Torri Antiche in Malta, extracted from Archivum

Melitense, p.17 (Malta -

1920). 31.

Cathedral Museum Mdina - Cathedral Archives MS.60. 32.

Archives of the Cathedral Museum, Mdina, Ms. 737 f.363 as quoted in

Mifsud, p. 17. 33.

For more information on Swabian castles in Italy see Itinerari Federiciani in Puglia - Viaggio nei castelli e nelle dimore di

Federico II in Svevia, edited by Cosimo Damiano Fonseca, (Bari -

1997). 34.

Archivo di Stato di Palermo

RC 49, f.51 as cited in Fiorini & Buhagiar, op.cit., p.443. 35.

Archives of the Cathedral Museum, Mdina,

Misc. 441,Quire B, ff.1-32 quoted in Fiorini & Buhagiar, op.cit.,

p.466 - NLM Univ. Ms. 84,

ff.366-636. 36.

National Library of Malta, University

Ms. 13, f. 356. 37.

Wettinger 1982-87; documentary references to ''Rocca'

are discussed in more detail in Fiorini & Buhagiar pp. 450-452. 38.

National Library of Malta, Archives of the Order of St. John

(A.O.M.) 1016, f. 157 (21 February 1693). 39.

A.O.M. 1016, f.480 (24 May 1701). 40.

A.O.M. 1017, f.90 ( 1717). 41.

A.O.M. 1016 f. 157. 42.

Fiorini & Buhagiar, op.cit., p.447. 43.

Cathedral Museum Mdina - Cathedral Archives MS.60. 44.

Fiorini, S., The 'Mandati' Documents at the

Archives of the Mdina Cathedral, Malta 1473-1539,

Mandati 2, f.262, p. 103

(Malta - 1992).

45.

ibid., Mandati

3, f.691, p.175. 46.

ibid., Mandati 3, f.623, (1538) p.170. 47.

ibid., Mandati 2, 160 (1527), p. 96; for definition of porta falsa see G. Grassi Dizionario

Militare Italiano p. 392 (Naples – 1835), ‘porticicciuola, piccola porta munita d’un rastrello di ferro, fatta

nel mezzo delle cortine, o sul angolo di esse, o vicino agli orrecchioni,

per andar liberamente e fuori della visita del nemico dalla piazza alle

opere esteriori’. The term Porta

del Soccorso was also used to describe a sally-port. 48.

ibid., Mandat 3, f.533 (1538), p.163. 49.

Abela., op.cit., p.29. 50.

Ganado, A., book

review of ‘Mdina,

the Cathedral City of Malta’ in the

Times of Malta (Wednesday 4 December 1996) p.21. 51.

Abela., op.cit., p.29. 52.

Archives of the Catheral Museum, Mdina, Misc.34,

ff.682v-3, cited in Mifsud, op.cit., p. 17 and Fiorini &

Buhagiar, op.cit., p.474. 53.

A.O.M. 1017, f. 41 (1716). 54.

National Library of Malta, University Ms. Vol. 187, f. 81 (1724). 55.

A.O.M. 1016, f.157. 56. Fiorini, op.cit., Mandati 1, f. 283b, p. 190; Mandati 3, f. 687v, p.199.

|

|||||||||||