The Development of the Bastion of Provence, Floriana Lines

by Stephen C. Spiteri

The

design and construction of the Floriana fortifications, one of the most

extensive and complex works of military architecture carried out by the

Hospitaller Knights in the Maltese islands proved to be a

lengthy and drawn out affair - a situation borne, primarily, out of the

ambitious nature of the undertaking, coupled with a perennially inadequate

allocation of resources necessary for the completion of the task, and a

host of technical difficulties encountered in adapting the site to the

design solutions imposed by the conventions of the bastioned trace.

It was

particularly the latter, compounded further by a continual improvement in

the power of siege artillery, and a parallel development in the art of

military architecture, that was to witness a number of interventions aimed

at 'correcting' the perceived,

and frequently acknowledged, weaknesses inherent in Pietro Paolo Floriani's

original design. Nowhere was this process of

rectification and adaptation so evidently manifest than along the

Marsamxett side of the Floriana enceinte, particularly at the Bastion of

Provence and its adjoining ramparts.

The

design and construction of the Floriana fortifications, one of the most

extensive and complex works of military architecture carried out by the

Hospitaller Knights in the Maltese islands proved to be a

lengthy and drawn out affair - a situation borne, primarily, out of the

ambitious nature of the undertaking, coupled with a perennially inadequate

allocation of resources necessary for the completion of the task, and a

host of technical difficulties encountered in adapting the site to the

design solutions imposed by the conventions of the bastioned trace.

It was

particularly the latter, compounded further by a continual improvement in

the power of siege artillery, and a parallel development in the art of

military architecture, that was to witness a number of interventions aimed

at 'correcting' the perceived,

and frequently acknowledged, weaknesses inherent in Pietro Paolo Floriani's

original design. Nowhere was this process of

rectification and adaptation so evidently manifest than along the

Marsamxett side of the Floriana enceinte, particularly at the Bastion of

Provence and its adjoining ramparts.

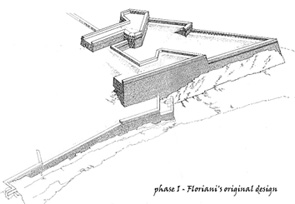

The

work of fortification, and re-fortification, along the Marsamxett enceinte,

aside from the addition of the faussebraye and the crowned-hornworks,

accounts for the larger part of the effort invested in the strengthening

of the Floriana defences throughout the late 17th and early 18th

centuries. An evaluation of the character and development of the design

of these defensive works must inevitably depart from an understanding of

Floriani’s original design and the shortcomings inherent therein.

Strategic

Considerations

From

a military engineers’s point of view, Malta in the age of gunpowder

fortifications offered few naturally endowed sites that gave themselves so

readily to the founding of a piazzaforte.

The nature of the local landscape rarely combined the requisites of

command and defensibility inherent in elevated sites with the vicinage of

a safe anchorage, the presence of an adequate water supply and a

topography congenial to the urban and social functions of a city.

Perhaps one of the few exceptions to this geographical reality was

Mount Sciberras, a mile long peninsula separating the Grand Harbour from

Marsamxett. Its potential as

a veritable sito reale was

immediately recognized by the Hospitaller Knights long before the actual

arrival of the Order in Malta - a commission of eight knights sent over to

inspect the Island in 1524 lost no time to point it out as the ideal site

for the Order's new convent.

This

opinion was reiterated many times by the Order's military engineers in the

course of the early half of the 16th century. Antonio Ferramolino,

Bartholomeo Genga, and Baldassare Lanci were among those who strongly

prescribed the Sciberras heights as the solution to the Order's defensive

problems but on each occasion the financial, political, or military

situation did not favour the implementation of any of the proposed

schemes. It was only after the Great Siege in 1566 that the

opportunity was found to build the desired stronghold and the new

fortified city of Valletta which quickly sprang up to the design of the

papal military engineer Francesco Laparelli did not fail to exploit the

potential of the site. By a

careful combination of man-made bastions and ramparts, and rock hewn

scarps, the rocky promontory was fashioned into a formidable fortress,

lauded and eulogized as a classic of the military engineer’s art.

Still,

Laparelli’s fortress only occupied part, albeit the highest area, of the

peninsula since the fortification of the whole promontory, down from Tarf il-Ghases up

to the spring at Marsa (some 3 Km) was then considered

too grandiose and costly an undertaking, requiring also too many men and

canon to garrison and defend. The

fact that Laparelli planted the land front of his fortified city half way

along the length of the promontory, however,

left a considerable stretch of unoccupied land at the neck of the

peninsula and ironically, it was this ‘left-over’ extent of ground

which was to feature so prominently in the defence of the fortress

throughout the course of the following two centuries.

The

reason for this occurrence lay inherent in Laparelli’s own rigid design.

For by the beginning of the 17th century, it had become difficult to

reconcile developments in technology and military architecture with the

plan executed in 1566. The increased range and effectiveness of artillery

called for a greater depth to the defences in order to prevent the

bombardment of those vital parts of the city.

Laparelli’s front, with its restricted bastions and narrow ditch,

and devoid of any protective

shield of outerworks, was particularly exposed to attack. The Knights

recognized that only substantial alterations and additions to the old

front could serve to remedy the situation.

The

solution that was eventually prescribed was the provision of a second

forward enceinte, one which enveloped the old front within a new outer

line of fortifications covering that same stretch of ground which had been

left outside Laparelli’s plan. The architect of this new scheme was the

Italian military engineer Pietro Paolo Floriani, who had been sent by the

Pope to help the Order undertake a complete reassessment of the island’s

fortifications following the threat of a Turkish attack in 1635. Although approved and quickly initiated, Floriani’s scheme came

in for much criticism from the very start. His ambitious project proved

more radical than anticipated and after his departure from the island the

Knights began to doubt its merits. Apprehension as to the total cost of

the undertaking and the conflicting opinions of a string of

leading engineers consulted for their advice meant that the project

dragged on in a dilatory and half-hearted fashion.

Still, the Order had invested so much resources in the building of

the Floriana fortifications that any abandonment of the scheme or its

substantial alteration was already unthinkable by 1640.

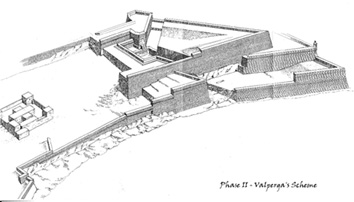

By

the time of the great general alarm of 1669, following the fall of Candia

to the Turks, the Floriana fortifications, although for their most part

laid out to Floriani’s original blueprint, were still in an incomplete

state and obviously constituted a weak point in the defences of the

convent. The task of bringing these works to completion and perfecting

their design fell on the shoulders of Count Antonio Maurizio Valperga,

chief engineer to the duke of Savoy who was invited to Malta by the Order.

His intervention (which was to prove one of the most consequential in the

development of the Island’s fortifications, producing the first ever master-plan for the

systematic defence of Valletta and the harbour areas) helped reshape

the Floriana fortifications with the addition of substantial supplementary

outerworks in the nature of a so-called faussebraye and a crowned-hornworks,

together with modifications to the bastioned front itself, all

intended to correct the long acknowledged faults inherent in Floriani’s

design.

Floriani’s

Scheme and its Failings

Ever

since Floriani had traced out his plan on site in 1635,

many serious flaws became apparent in the layout of the new

fortifications. The weaknesses ingrained in the design, and the problems

that these were perceived to entail for the proper defence of the new

works, only began to be really appreciated

once the fortifications began

to take shape, slowly fashioned out as these were from the living rock.

That these defects were not immediately clear on plan is brought

out by the praise lavished on the design by Firenzuola’s when he was

consulted for his views on the matter. Firenzuola actually commended those

elements in the design which eventually proved to be the main cause of

concern. (1)

The main shortcomings were seen to arise from the fact that the front was

laid out along a straight line and that the left ravelin was overlooked by

high ground. More alarming, however, was the relative weakness of the

extremities of the front and their adjoining lateral walls.

once the fortifications began

to take shape, slowly fashioned out as these were from the living rock.

That these defects were not immediately clear on plan is brought

out by the praise lavished on the design by Firenzuola’s when he was

consulted for his views on the matter. Firenzuola actually commended those

elements in the design which eventually proved to be the main cause of

concern. (1)

The main shortcomings were seen to arise from the fact that the front was

laid out along a straight line and that the left ravelin was overlooked by

high ground. More alarming, however, was the relative weakness of the

extremities of the front and their adjoining lateral walls.

An

evaluation of these shortcomings, and consequently of the significance of

later interventions, can

only follow from an understanding of Floriani’s original design. This,

however, is easier said than done for accurate details of Floriani’s

original scheme as actually traced out by him on site in relation to the

existing nature of the terrain are rather scanty and most of

the information must, as a result, be deduced from a study of the

architectural fabric and the reports produced by successive engineers.

Although

several plans attributed to Floriani have survived in the Vatican Library

many of these seem to be proposals rather than what one would term

‘record plans’ of the executed design.

Indeed, all the plans tend to defer in their treatment of various

salient details though all agree on the overall character of the scheme.

The principal elements of the land front, the most critical part of

the enceinte, comprised a large central bastion, supported by two demi-bastion

and two large ravelins, a ditch and a narrow covered way with star-shaped

places-of-arms.

Floriani

had composed his whole design around the concept that the bastions on the

Valletta front were too small and restricted to allow a rearguard action.

He therefore produced a bastioned front with component parts that were

much larger than those of the mother fortress. However, the

width of the peninsula at Floriana, being roughly equal to that of

the old Valletta front, only allowed for three large bastions.

As a matter of fact, his idea was not all that original for a

preference for a three-bastioned solution was mooted many times in the

course of the 16th century - Ascanio della Cornia, Fratino and possibly

even Genga and Lanci had all envisaged this type of design for a fortress

on Mount Sciberras. The massive form of Floriana’s central

retrenched bastion, however, only just permitted two other supporting demi-bastions,

but these, to be adequately accommodated, had to be pushed so much to the

sides that they hung on the precipitous slopes overlooking the Grand

Harbour and Marsamxett, presenting a high profile on the flanks, vulnerably

exposed to bombardment from the surrounding heights. The

fronts straddling the harbours, although necessary to deny

the enemy a foothold on the Sciberass penibsula, similarly provided

a high profile, for lacking a ditch and the protection of a counterscarp,

these were easily overlooked and enfiladed.

The

main front itself, sited approximately 800 canes from the ditch of Fort

St. Elmo occupied the ridge of a plateau overlooking the low lying

marshland of Marsa. This was

the highest escarpment south of the old Valletta front and its adoption as

Floriani’s main line of defence was a natural logical choice. A stretch

of high ground in front of the Capuchin convent, however, could not be

incorporated into his symmetrical design and as a result it immediately

came to constitute, as acknowledged by Floriani himself, a direct threat

to the left ravelin.

Even

the vast space enclosed by the new enceinte was seen to constitute a

defensive problem for it offered the defenders no cover in retreat. Floriani originally intended this esplanade

to serve as an area of refuge for the rural population in times of

invasion, but subsequent military planners deemed that this space

had first to fulfill military priorities.

During the 1640s military

engineers put forward a variety of remedies for this situation.

Louis Viscount de Arpajon and Louis Nicolas de Clerville

recommended that the esplanade be covered by a hornwork emanating from

Porta Reale, the main entrance into the city.

Clerville also proposed

the construction of a number

of earthen and palisaded redoubts while the Marquis of St. Angelo actually

sought to retrench the whole area within two sets of straigtht walls,

virtually converting the Floriana enceinte into a sort of large crownwork.

The only intervention that was actually implemented, however,

was the construction of four counterguards and a lunette, supported by an

advanced ditch and covertway, designed by the Marquis of St. Angelo, but

these were intended mainly to reinforce the old Valletta front rather than

secure the open space.

Faced

with this inflexible and pre-cast architectural ensemble, Valperga chose

to react much in the manner of Floriani,

projecting new works ahead of the old enceinte rather than

interfere with the original design. Being himself an adherent of an

aggressive form of defence as practised all’olandese,

Valperga boldly pushed out the main front by means of a braye and a

crowned-hornwork. The latter,

he placed on the left side of the enceinte to occupy the high ground

dominating St. Francis Ravelin. Only

on the right demi-bastion of the Floriana front was he compelled to modify

the original layout, at the Bastion of Provence.

The

Bastion of Provence

The

most inadequate of all the elements of the Floriana enceinte proved to be

the two extremities of the linear front, the demi-bastions and their

adjoining lines of lateral walls, particularly the right demi-bastion

overlooking Marsamxett, known as the Bastion of Provence. The problem with

this demi-bastion was that it had too acute a salient while its long right

flank was not adequately covered from adjoining works, leaving large areas

of dead ground which could not be defended or covered by artillery fire.

Its initial form, however, is not outrightly clear, both because of

the later alterations and also because of the scarcity of

documentary evidence. All existing plans differ as to the details of this

bastion. All, however, reveal a tiered approach dictated by the sloping

nature of the ground. Plan

Barb. Lat. 9905/3 and I

seem to be early proposals terminating in a flanking battery on the

Marsamxett side of the enceinte.

The

only plan which appears to be

actually documenting the early stages of the Floriana fortifications, and

possibly Floriani’s executed design,

is Barb. Lat. 9905/4. This shows a detailed measured drawing of

works in progress. Although

undated it was definitely executed prior to 1640-45 for the counterguards

added by the Marquis of St. Angelo do not feature on the adjoining

Valletta land front. That this plan records the works in progress is also

borne out of two other factors, namely that

i)

various parts of the enceinte are shown in dotted lines, indicating

that work on these had not yet started and

ii)

the tenailles in front of the land front curtains,

and three of the flanking batteries, are missing, implying that the

depth of the walls, carved out as these were from the bedrock had not yet

reached the desired level for these features to be hewn out.

Eventually these features would appear when carved out of the living

rock as can still be seen to this day.

Perhaps

the closest one can arrive to Floriani’s

actual design, is a small plan sketched in ink and attached to his

report dated 29th September 1636, which he prepared as written

instructions, avvertimenti, to be followed by his assistant the Architect

Buonamici, after his own departure from Malta.(2)

This sketch plan shows basically the same layout

illustrated in Plan 9905/4, but having a stepped two-tiered salient

isolated from the interior works by a ditch.

Plan

9905/4 also clearly indicates why the Bastion of Provence was considered

to be the weakest part of the land front.

For one thing it was the smallest of the three bulwarks on the

Floriana front; secondly, it had an acute angled salient and a relatively

narrow neck or gorge, narrower, in fact from those of the main

bastions on the older Valletta front.

Internally the gorge of the bastion was itself sealed off with a

cramped ritirata. The provision

of internal, secondary lines

of defence, in the form of low demi-bastioned ramparts was a

characteristic feature of Floriani’s works, and is seen employed in all

the major elements of his design including the two large ravelins or

mezze lune. This same

approach is also noted in his earlier works and is already well spelt out

in his treatise Difesa et ofesa

delle piazze.

The

restricted span of the gorge in the Bastion of Provence only allowed for a

small and cramped arrangement incapable of containing a sizable defensive

force. The internal bastions and curtain forming the ritirata

presented a very restricted front with limited potential for enfilading

fire. Floriani seems to have favoured retired flanks and pronounced

orillions and similar solutions can be found in his earlier proposals for

the fortification of the Cittadella of Ferrara in 1629-30.

The

sloping nature of the site on which the Bastion of Provence was built called for a stepped design to adapt it to the lie of the land.

The highest part of the work was inevitably the left flank facing the

centre of the front. This was occupied by a small iregularly shaped

bastion known as San Salvatore, the

right elongated face of which formed part of the

ritirata within the Bastion of Provence,

while its left face and flank

overlooked the adjoining curtain later known as Notre Dame Curtain with

its Porta dei Pirri.

The parapet along the face of the Bastion of Provence descended in

three unequal steps towards the salient and then turned sharply north to

form a very elongated flank facing the sea towards Msida. The same

treatment is encountered in Floriani’s inked sketch attached to the

29th September report.

La

Vittoria Bastion

It

was the right flank of the Bastion of Provence that was particularly

exposed to artillery attack and assault since it presented a high exposed

target unprotected by ditch and counterscarp. Above all, it was

practically unflanked except for the provision of a small battery capable

of mounting only a single cannon, 'un

piccolo fianco capace d’un sol canone'.

(4)

This

flanking device features in Floriani’s plans but seems to have been

included merely as an after-thought once it became all too clear that the

excessive length of the right flank would create a significant

weakness in the defence. That

it was considered inadequate is attested by the reports of both

Giovanni Bendinelli Pallavicino and Louis

Nicolas de Clerville, both of whom recommended that the flank of

this bastion be protected by the addition of a new low work in the form of

a bastion or a large traverse capable of delivering the necessary

enfilading fire.

The

resultant heightening of the

ramparts gave the bastion a characteristic profile quite distinct from the

other two bastions on the Floriana landfront since the walls on the north

flank of the bastion of Provence are higher at the salient than at the

gorge. This characteristic feature

is also clearly illustrated in a stone model

now at the Fine Arts Museum in Valletta which shows Valperga’s

and Grunenburgh’s proposed

alterations to the Bastion of Provence. Then, as now, architects and

military engineers made use of scaled models of fortification to present

to their patrons.

Usually such models were made of wax - a modello di cera, for example, was presented to Knight Galilei

to forward to the Grand Master.

(8)

Dal

Pozzo, in his history of the Order, makes a specific reference to

Grunenburgh's use of 'modelli

in pierta dell'opere principali' in his efforts to 'completare la

Floriana'.

This

interesting stone model also illustrates how Valperga’s managed to

enclose the fragile acute salient of the bastion within part of the

faussebraye and reinforced the flank with the construction of a new

bastion (La Vittoria) and a bassoforte

(a kind of counterguard) termed la

Conceptione. The construction and development of the new bastion 'La

Vittoria' is documented in various plans, Valperga’s own report and

Grunenburgh’s stone model. A careful study of Valperga's report shows

that various historians have been is mistaken in identifying the bastion La Vittoria with

the low work adjoining the faussebraye. It appears that the name La

Vittoria originally referred to the right demi-bastion of the ritirata

within the Bastion of Provence. This small internal work originally had a

more acute salient but seems to have been redesigned and its face

extended out on the flank of the bastion of Provence to allow for an

adequate artillery platform. Evidence

of the incremental development of the Vittoria bastion, illustrating the

distinct stages in its design, is encountered in many places throughout

the structure. Possibly, the

most archaic remnant of the earliest form of the defences in the area, is

the rock-hewn footing of the salient of a rampart, enclosed within one of

the rooms of the bastion’s casemated interior - this may have been the

narrow flank capable only of mounting a single gun, mentioned in the

documents. Another, is a section of a cordon running above the opening of

an arched tunnel within the bastion. This bears witness to the fact the

internal wall in question was originally the outer face of a rampart.

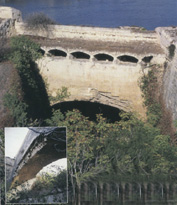

In

order to ensure that the area at the foot of the salient of Valperga’s

new bastion did not construe dead

ground, the Italian military engineer proposed that a large arched

opening, what he terms the arcone, be made in the wall of the Bastion of Provence to allow guns

in the left flank of the internal

ritirata to provide the required enfilading cover.

(9)

This large vaulted and skewed arcone

presents one of the most interesting features of the fortifications in the

area. The arch practically spans the width of the fosse of the ritirata

and contains, internally, a vaulted gallery which leads to the

countermines built into the terrepleined body of the bastion. Its

construction, if we are to believe Pietro Paolo Castagna is the work of

the Maltese capomastro, or architect, Giovanni Barbara ( Degiorgio, The

Malta Independent - 28/3/1993.) and was finally completed in 1726.

George Percy Badger, writing in his Description of Malta and Gozo

(1838) was impressed by this ‘very

massy arch’ and the ‘architecture of this piece of workmanship’ so

‘very much admired by

conoisseurs; the curve is of

a tortuous and oblique form, and extends over a space abut thirty feet in

width.’ (10)

The

Bassoforte della Concettione

The

rocky ground at the foot of the flank of the Bastion of Provence, facing

Marsamxett, was fitted with a low platform , referred to in the documents

as the basso

forte detto la Conceptione. This

served mainly as a form of counterguard intended to protect the flank of

the bastion and the salient of the fausse-braye then under construction.

It comprised largely a revetted earthern work, since, having been built

down at sea-level it could not be carved out of rock, like most of the

adjoining ramparts. The

extent of the earthen

content used in its construction is witnessed by the abandunt

garden that now occupies the site. The

use of the site as a garden, however, is not a modern practice. In 1719,

the Knight Frà Martino Muaro Pinto petitioned the Grand Master for the use

of the 'giardino e casmento chiamato

della concettione sito nella

piazza bassa del beluardo della Concettione delle fortificationi Floriana',

vacated on the death of Frà Gio. Battista de Semaisons. By the late

19th century, the garden was more popularly known as Giardino Se Maison. (11) A house seems to have occupied part of the

bassoforte. It was still in existance during the 19th century,

'generally hired as a country-seat by some of the gentry of the island',

for both the house and its garden were considered

'...

a delightful spot, possessing a

most charming view of the Quarantine Habour, the Pieta, and the country

beyond'. The garden though small, was

'laid out with exquisite taste, and ... well supllied with flowers, the adjoining battlements covered with ivy, giving it at a

distance a most beautiful

appearance. house belongs to government, and is Beneath the bastion which

extends alomg the poor asylum to this villa.'

The

rocky ground at the foot of the flank of the Bastion of Provence, facing

Marsamxett, was fitted with a low platform , referred to in the documents

as the basso

forte detto la Conceptione. This

served mainly as a form of counterguard intended to protect the flank of

the bastion and the salient of the fausse-braye then under construction.

It comprised largely a revetted earthern work, since, having been built

down at sea-level it could not be carved out of rock, like most of the

adjoining ramparts. The

extent of the earthen

content used in its construction is witnessed by the abandunt

garden that now occupies the site. The

use of the site as a garden, however, is not a modern practice. In 1719,

the Knight Frà Martino Muaro Pinto petitioned the Grand Master for the use

of the 'giardino e casmento chiamato

della concettione sito nella

piazza bassa del beluardo della Concettione delle fortificationi Floriana',

vacated on the death of Frà Gio. Battista de Semaisons. By the late

19th century, the garden was more popularly known as Giardino Se Maison. (11) A house seems to have occupied part of the

bassoforte. It was still in existance during the 19th century,

'generally hired as a country-seat by some of the gentry of the island',

for both the house and its garden were considered

'...

a delightful spot, possessing a

most charming view of the Quarantine Habour, the Pieta, and the country

beyond'. The garden though small, was

'laid out with exquisite taste, and ... well supllied with flowers, the adjoining battlements covered with ivy, giving it at a

distance a most beautiful

appearance. house belongs to government, and is Beneath the bastion which

extends alomg the poor asylum to this villa.'

Early 18th century plans of the Floriana fortifications show the Bassoforte to have been heavily countermined. The salient of the bassoforte, adjoining the faussebraye was raised to a greater height than the remainder of the work.

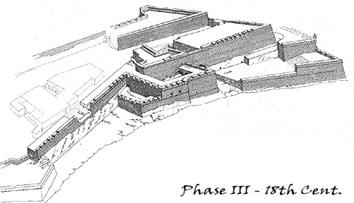

Grunnenburgh’s

Involvement.

Completion

of a scheme

The

final phase in the development of the fortifications of the area in

question was undertaken under the supervision of French military engineers

during the 1700s, particularly by Mondion. This in actual fact only construed a

continuation of Valperga's scheme and Grunenburgh's recommendations. These

were the works which refashioned the fortifications and gave them the form

they have to day. Primarily these included

i

) the re-alignment of the Polverista curtain; this was pulled back to

enable the formation of a flank and piazza bassa in the north side of the

bastion 'la Vittoria'

ii)

the raising of the height of the curtain and adjoining bastion with the

construction of a continuous ranged of vaulted casemates

iii)

the re-design of the San Salvatore Bastion to accommodate a

new retrenchment

within the body of the

Bastion of Provence parallel to the Marsamxett face; this involved the

partial demolition of the curtain wall of the old ritirata

- this retrenchment spanned all the way to the rear of the

Ospizio area.

Most

of these works were completed throughout the course of

the 1720s as attested by the coat-of-arms and date (1723) inscribed

on Polverista curtain.

The

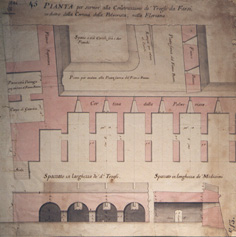

Polverista Curtain and the Gunpowder Factory

The

curtain wall adjoining La Vittoria Bastion to the north was known as the

Polverista curtain. This

title was applied to it after the construction of

a gunpowder factory on the site which was erected there in the late 17th century following its removal from its old site within

the fortress of Valletta, a re-location obviously inspired by the need to

abolish such a dangerous practice. As a matter of

fact, the Valletta powder factor, the ‘Luogo

dove si fa la polvere’ was originally located in the vicinity of the

Prigione degli Schiavi (slaves’ prison) on the site of the

present Cottonera block. This actually blew up on 12 September 1634, killing 22 people and seriously damaging

the nearby Jesuits College and church.

The Order's records show that by 1665, the

Knights were still looking for 'un luogo fuori della

città per raffinar la

polvere'. (14)

In that same year, however, the Congregation of war , determined to resolve the situation,

instructed the resident military engineer, Blondel, to draw up plans for a 'casa

accomodata per fare e raffinare la polvere' which was to be built 'nella

floriana dalla parte che riguarda il porto di Marsamscetto'.

The

new polverista was quickly built and already producing powder by 1667 .

The building appears to have consisted of a structure enclosed within a

high-walled rectangular enclosure.

It

was equipped with tre molini

used for the production of zolfo

e salnitro . By the early 18th century

it was also served

by a number of magazines or ‘mine’

situated in the vicinity, one of which

was known as' dell’Eremita' and another 'del Tessitore'.

Soon after the construction of the casemated curtain nearby in the

1720s, the master in charge of the Polverista, Giovan Francesco Bieziro proposed to the utilization of the 'trogli nuovamente fabbricati'

for the production of gunpowder. By the beginning of the 18th century, the

Polverista had became a prominent

landmark, and is seen on many of the plans and views of Floriana. This is

hardly surprising for it was then practically one of the largest buildings

within the then largely barren enclosure of Floriana.

By

1725, works on casemates near the polverista were proceeding at

the rate of 250 scudi a week (1725). A commemorative plaque on the polverista curtain itself, set

between the arms of the Order and those Grand Master de Vilhena bears the

date 1723 and seems to indicate that work on this curtain wall had been

brought to completion by then. The Order's records show, however, that in

1758 workers were still

labouring to cut away 'un labbro di rocca forte che rimaneva sotto la

cortina ... (del')Opsedale delle donne' (1758).

This

work came to consist of a line

of bastioned ramparts spanning from San Salvatore Bastion to the salient of St. John's Counterguard.

The new work necessitated the redesign

of part of the bastion of Provence, wherein the Marsamxett side of the San

Salvatore bastion was re-aligned parrallel to a new fosse excavated within

the body of the bastion of Provence. In the process, the

left half of the vecchia ritirata was swept away to make room for

the new ditch. The archival

records show that work on this entrenchment was still in progress in 1733,

particularly along the 'contrascarpa

al nouo interiore recinto destra della Floriana.'

The

'Ospizio'

A

concern for the welfare of an

aging population drove the Order to

provide shelter and food for indigent old men and women within the newly

founded town of Floriana. In 1729, the Grand Master, wanting to make use

of the large casemates 'nuovamente fabricate al Florina in sopra della polverista' to establish 'un

spedale d’Uomini vecchi e invalidi,'

ordered the engineer

Mondion 'di

accomodare caserne ...

facendo nella loro altezza altri piani o solaci mezzani, scale, diversi

muri divisori, ... una capella decente adornata, ... scavando nella rocca

una gran conserva d’acqua.'

In the following year, Vilhena, encouraged by the success of this

institution, ordered the establishment of a similar hostel 'a

favore delle femmine povere e vecchie delle caserne della nuova cortina

sotto della polverista con mura sicure, comprendendovi un gran spazio per

cortile orto. e nell’interiore si fecero le divisioni convenevoli, la

cucina e l’avatoio, cisterne e insomma tutte le commodita necessarie nel

modo che si vedono attualmente stabiliti.'

A

concern for the welfare of an

aging population drove the Order to

provide shelter and food for indigent old men and women within the newly

founded town of Floriana. In 1729, the Grand Master, wanting to make use

of the large casemates 'nuovamente fabricate al Florina in sopra della polverista' to establish 'un

spedale d’Uomini vecchi e invalidi,'

ordered the engineer

Mondion 'di

accomodare caserne ...

facendo nella loro altezza altri piani o solaci mezzani, scale, diversi

muri divisori, ... una capella decente adornata, ... scavando nella rocca

una gran conserva d’acqua.'

In the following year, Vilhena, encouraged by the success of this

institution, ordered the establishment of a similar hostel 'a

favore delle femmine povere e vecchie delle caserne della nuova cortina

sotto della polverista con mura sicure, comprendendovi un gran spazio per

cortile orto. e nell’interiore si fecero le divisioni convenevoli, la

cucina e l’avatoio, cisterne e insomma tutte le commodita necessarie nel

modo che si vedono attualmente stabiliti.'

The

House of Industry

This

building was erected by Grand Master de Vilhena and was originally

intended 'as a Conservatory for poor girls, where they were taught to do a

little work, and in other respects to perform all the offices of nuns'.

In 1825 this establishment

' underwent an entire reform

and until lately was in a very thriving condition as regards of its

inmates. A great diversity of labour was done here, such as weaving,

knitting, making lace, sewing, washing, shoemaking, straw-plaiting, segar-making,

and many other very useful branches of female manufacture

...

The lower part of the back side of the building forms a barracks

for a regiment of the British garrison.'

(1)

Letter from Barberini to Chigi, Rome 16. Feb. 1631,

‘...

il quale (Firenzuola) ha lodato

sommamente il pensiero del Sig. Floriani, et ancora .... ha bene

lodato piu’ difficile et quasi impossible ad essere attacati ...

nell’altra I due beluardi posti vicinal al mare’.

(2)

Vatican Library, Fondo Chigi, Ms R I 25, f.335.

(3)

AOM

261, f.26

(4)

AOM 6554, f.117

‘...

e’ piu’ difettoso, poiche formato sopra una linea retta quanto e forte

nel beluardo di mezzo tanto e’ debole, e mancante di difesa nelli mezzi

beluardi delli lati, ma assai piu’ in quello che riguardo il porto di

Marsamxetto per non haver altra difesa che un picciol fianco capace d’un sol canone, dal quale resta formato

un angolo morto, in altre per venir infilato da diversi monticelli vicini,

et sopra tuuto per l’imperfettione del sito che

da commodita all’inimico d’avvicinarsi coperto al corridore, et

d’avvinarsi lungo il mare nello spatio che li resta di terreno fin a

scarpellare il muro con lasciar delusa tutta la robustezza et resistenza

della fronte.’

(5)

AOM 6554,

f.120v. ‘...

sino al termine della ponta della vecchia ritirata, affinche questa

eccessiva altezza di muro non impediscono li tiri della detta ritirata’.

(6)

ibid., f.119, ‘...

La nuova porta cominciata nella

cortina tra i due beloardi della ritirata si fara di larghezza palmi nove

et altezza sino sotto il dado dell’imposta del doppio portico di forma

quadra et compilo che sara il doppio portico conforme al disegno (?)

sopra si mettera un palmo o due di terra piu o meno se sara bisogno accio

rimanga il muro fatto della cortina con suo parapetto franco senz obligo dêalzare

detta cortina - ma ben alzare al novo fianco cominciato dal detto bastione

della Vittoria al pari di detta cortina e non piu et unire di semplice

muro il parapetto di detto fianco al pari di quello della detta cortina

con suo terrapieno necessario.’

(7)

ibid., f. 119, ‘... Avanti

le due faccie et cortina della ritirata che si sta travagliando nel corpo

del vecchio bastione di provenza si fara una fossa di larghezza di sei in

sette canne et della tera che pervenira da detta escavatione si portara

per terrapienare il beloardo detto della Vittoria et cortina attigua sopra

delle portico, che avanzandovi

terra con quella che converra abassare nella ponta del detto bastione di

provenza questa sêimpiegara parte nel basso forte della conceptione

et per riempire i vacui nel corpo della falzabraga causati della vecchia

fortificatione.’

(8)

AOM 6554, f.17.

(9)

ibid, f. 120, ‘...

Il vecchio muro del beloardo di provenza che guarda il mare ove s’unisse

con la faccia nova del bastione della Vittoria; al piede di questo si fara

un arcone largo di quattro canne (8

metres) et alto palmi undici, sopra l’imposta, et in maniera

aggiustato che non possa impedire i tiri che perveniranno dal fianco

opposto della ritirata, accio da questi venga la nuova ponta di detto

bastione della Vittoria ben fiancheggiata nel suo piede,

(10)

Badger, G. P., Description of Malta and Gozo, Malta 1838, Facsimile

Edition, Malta, 1989, p.201-202

(11)

AOM 1015,

f.347,

‘... incaricati di far visitare, e stimare il guasto cagioinato dal

fulmine nel Giardino Se Maison nello scorso Ottobre .’

(12)

AOM

6554, f.

199-199v.

(13) ibid., f.200, ‘... Ala falsa braga sopra la concetione, si deve levare una fiilata per fuori acio si possa dare piu declino al parapetto, questo si fara cominciando dalla guardiola sino al risalto che vie al stremita della cortina, che comprende una faccia, un fianco et una cortina’;

f.176

‘... per la parte de Marchemuchette, si halla de minuendo

y abasado parte del baluarte de Provenza que assi lo dispuso il S.

Conte Valperga, para que a la retirada del no le empidiesse la vista y

fuego a la campana, como a la falsabraga y glacis de la estrada encubierta,

que sera bueno de perfeccionar; assi por las racones referidos, como de

que no podera dominar con tantos ventasas la ultima retirada, que forma

una cortina y medio baluarde, que se determina a la mar’.

(14) AOM 261, f.26.