The Hospitallers in Rhodes

by Stephen C. Spiteri

(Extracted from Fortresses of the Knights)

With the occupation of Rhodes, the Hospitallers did not only acquire a new base from where to organize their military activities but also a little island kingdom. For with Rhodes came the rulership of the surrounding islands of Nisyros, Symi, Halki, Alimonia, Telos, Kalymnos, and Leros. In 1313 the Order also took possession of the islands of Karpathos and Kassos, disturbing the rule of Andrea Cornaro who induced Venice to intervene.

Not long after the transfer of the Orderís convent from Cyprus to Rhodes, the Hospitallers were soon attracting Turkish attention and Osman, one of the Muslim princes on the Turkish mainland, unsuccessfully attacked their island base in 1310. The Hospitallers, however, were quick to assert their naval control over the Aegean and, by 1320, they had won two important victories over the neighbouring Turkish emirates. They even secured and temporarily held a small number of castles on the Anatolian mainland itself and for the next century Rhodes was able to prosper in relative peace. Before 1306, Turkish razzias and slave-raiding had severely reduced the population of the Dodecanese islands. In Rhodes, an island 80 km long and 38 km wide, the number of inhabitants had dropped to well below 10,000 and much of the fertile lands had fallen out of cultivation.

The

Hospitallersí first task once they had taken control of the islands was

to repopulate them with Latin settlers and develop their commerce and

agriculture so that men and supplies would be available for the defence of

Rhodes. Farms, mills, and

agricultural estates were leased out in emphyteusis or in perpetuity.

In 1316 the fertile volcanic island of Nisyros was granted as a

fief to the Assanti family of Ischia, for which they owed the service of a

galley (an obligation which was later commuted for an annual sum of 200

florins in 1347) and in 1366, the islands of Kos and Telos were granted to

Borrello Assanti, burgensis of Rhodes, on condition that he was to

erect a watch-tower on the little island of Alimonia, near Halki.

Nevertheless, the number of men who actually settled down

permanently on Rhodes, especially fighting men, remained small.

In 1313 the Order offered land and pensions to any westerners who

would settle as soldiers or sailors in Rhodes.

The statutes of 1311 and 1314 projected a force of 500 cavalry and

1,000 foot soldiers to serve as a permanent garrison in Rhodes while the

number of brethren in the East stood between 200 and 350.

The Greek inhabitants were also involved in the defence of the

islands and had to perform servitude in the building of fortifications.

On Kos, for example, the inhabitants were forced to fortify the suburbium

in 1381.

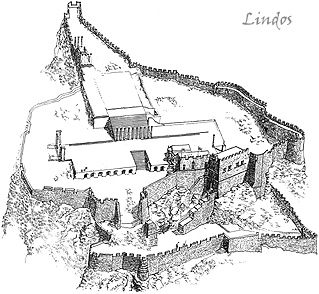

Each district, or castellania, had a castle under the command of a Hospitaller captain to which the rural population could retreat in times of danger, though most of the fortifications scattered around Rhodes and the neighbouring islands, with the exception of a few like Lindos, Pheraclos, Horio (Kalymnos), and Platanos (Leros) were neither powerfully built nor large enough to withstand determined attacks. Indeed, in times of crisis, many of these castles were actually abandoned and the inhabitants shipped off to the safety of Rhodes or the nearest impregnable fortress such as happened in 1470 and 1475, when the population of the islands of Telos and Halki were evacuated to Rhodes.

To ensure that

Rhodes was governed effectively, it was divided into a number of

castellanies.

The Castellania of the city of Rhodes included the

strongholds and villages at Trianda, Psinthos, and Philerimos; the towers of St Etienne, Faliraki, Afandou, and Massari; the

hamlets of Marista, Salia, Katangaro, Ermia, Eleoussa, Arhipolis, Platania,

Malona, and Kamiro; and the fortified monasteries of Aghios Ilias and

Tsambika.

The castles and villages of Koskinou, Archangelos, and Kremasti

were autonomous and had to arrange for their own defence. In 1479 the castellany of Pheraclos was set up and it came to

include properties which were formerly part of the castellany of Rhodes;

the castles and villages of Pheraclos and, Archangelos, and some hamlets.

The castellany of Lindos consisted of the castle and burgus

of Lindos, the castles and villages of Asklipion and Lardos, the towers of

Pefka, Aghios Yorghios and Gennadion, and the hamlets of Pilona and

Kalathos. In 1475 it was

decreed that Ďal Castello di Lindo ridurre si dovessero i Casali di

Calatto, di Pilona, di Lardo, di Steplio (Asklipion) e di Ianadi (Gennadion).í

Askiplion was detached from the castellany of Lindos in 1479 and,

together with the castle and village of Vathy, formed into a separate

administrative unit.

The castellan of Lahania was responsible for the village and castle

of Lahania, the towers at Aghia Marina, Cap Lahania, and Cap Vaglia

together with the hamlets of Tararo, Tha, Defania, and Efgales.

The castellany of Kattavia consisted of the village and stronghold

of Kattavia and the hamlet of Messangros.

The castellan of Apolakkia governed the castle of Apolakkia and its

village together with the other hamlets of Arnitha, Profilia, and Istrios.

In 1479 this district was amalgamated with that of Monolithos.

The castellany

of Sianna consisted of the castles and villages of Sianna, Telemonias, and

originally, even Monolithos and the towers of Glifada, Amartos, and Cape

Armenistis.27

In all, there appear to have been 20 castles on Rhodes. Of these, however, the ones at Lachania, Laerma, Psinthos,

Apollona, Salakos, and Trianda have disappeared with time and only a few

scanty remains survive of others, such as Kattavia, Apollakia, and Sianna.

The island of Kos, the largest of the archipelago after Rhodes, was also divided into a number of districts: Narangia, Pyli, Kefalos, and Andimacchia. Kefalos castle could only provide refuge against minor raids and its inhabitants had to retreat to the safety of Narangia in 1504.

At the time that the Order invaded Rhodes, the Hospitallers regarded the island as a base from where military operations could be launched for the recovery of the Holy Land. However, growing Turkish power led instead to a policy of resistance and to the defence of the Latin possessions in the eastern Mediterranean.

As the Ottomans advanced farther into the Balkans, the Order became increasingly involved in the defence of Greece and after 1356 there were even proposals which favoured establishing the Hospital on the mainland.

By 1402, the

Hospitallers had realistically decided that large-scale operations in

Greece were beyond their resources and instead decided to concentrate

their efforts at Smyrna, but the city did not last for long and in July of

that same year it was destroyed and dismantled by the Mongol ruler, Timur.

After the initial Turkish counter-attacks of 1310-12 and 1318-19, Rhodes enjoyed periods of comparative peace and there was no major assault on the island until the unsuccessful Egyptian Mameluke campaigns of 1440 and 1444. The Mamelukes had already invaded Cyprus in 1428 and, after the fall of Constantinople in 1453 to Sultan Mehmed II, Rhodes became the easternmost Christian outpost in the heart of an ever-growing Turkish empire. Thereafter, the retention of the Orderís position in the Aegean depended on the capacity of Rhodes to resist major assaults and the re-fortification of the city became almost unceasing. In 1480 Mehmed besieged Rhodes but the fortress held out heroically under the able leadership of Grand Master DíAubusson and the Turks were forced to withdraw.

After 1480 Rhodes was relatively safe again for a while because of the death of Mehmed in 1481 which

threw the Ottoman empire into chaos, diminishing the threat to

Christendom.

One reason for this was that for much of the reign of Bayezid II (Mehmedís

successor) the Hospitallers played host to his brother Jem, a pretender to

the Ottoman sultanate.

Bayezid was thus content to pay for his brother to be kept in the

West and to refrain from hostilities.

Work on the fortifications of Rhodes, however, continued unabated

and by 1487 massive gunpowder fortifications had begun to take shape

around the cityís enceinte.

By the opening

decades of the sixteenth century, however,

Rhodes and the surrounding islands were once again subjected to an

increasing pressure of raids and the Hospitallers were forced to

hold the island in a perpetual state of military readiness.

Their own continual aggressive preying on Muslim shipping meant

that the Turks could not afford to ignore an island that commanded the sea

route to Syria and Egypt and, in 1521, Suleiman the Magnificent, after

capturing Belgrade, turned his attention to Rhodes.

This time the Turks returned with heavy artillery and some 200,000

men. Grand Master Philip

Villiers de LíIsle Adam, a Frenchman, inspired another valiant defence

but after six months of fighting and bombardment, manpower, munitions, and

morale had run low. With no

hope of any assistance from the West, the Order was forced to surrender

and accept the good terms offered to it by Suleiman.

On 1 January 1523 the Hospitallers

left Rhodes, taking with

them all the possession and weapons they could carry away.

By the opening

decades of the sixteenth century, however,

Rhodes and the surrounding islands were once again subjected to an

increasing pressure of raids and the Hospitallers were forced to

hold the island in a perpetual state of military readiness.

Their own continual aggressive preying on Muslim shipping meant

that the Turks could not afford to ignore an island that commanded the sea

route to Syria and Egypt and, in 1521, Suleiman the Magnificent, after

capturing Belgrade, turned his attention to Rhodes.

This time the Turks returned with heavy artillery and some 200,000

men. Grand Master Philip

Villiers de LíIsle Adam, a Frenchman, inspired another valiant defence

but after six months of fighting and bombardment, manpower, munitions, and

morale had run low. With no

hope of any assistance from the West, the Order was forced to surrender

and accept the good terms offered to it by Suleiman.

On 1 January 1523 the Hospitallers

left Rhodes, taking with

them all the possession and weapons they could carry away.